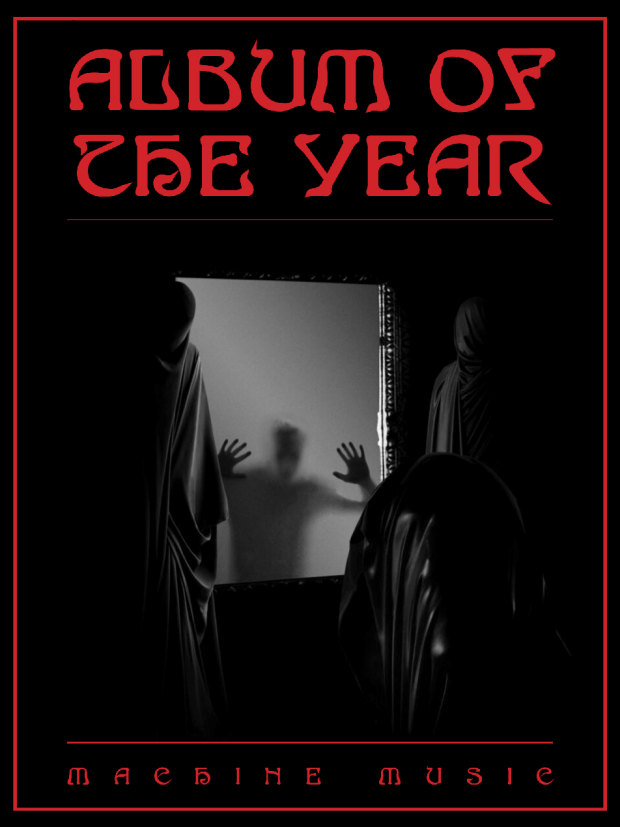

MACHINE MUSIC'S ALBUM OF THE YEAR: AN INTERVIEW WITH AEVITERNE

Artist: Aeviterne

Album: The Ailing Facade

Label: Profound Lore Records

Favorite Song: Every damn song in the damn album

The Bare Bones: The Ailing Facade is the debut full length album from New York-based death metal band Aeviterne, made up of Ian Jacyszyn (Miasmatic Necrosis, ex-Castevet), Garrett Bussanick (ex-Flourishing), Sam Smith (Artificial Brain, Luminous Vault), and Eric Rizk (ex-Flourishing).

The Beating Heart: Well, there's a lot of ground to cover this time around. First, this interview was supposed to come out in, a 2022, with the year's list with the other two 2022 AOTY interviews (SkyThala and Scarcity), but things just happened the way they did and here we are. Better late and all that. Second, this is my belated opportunity to pay homage to what really is one of my favorite metal albums in recent years, one that, to me (and this actually comes up in the interview) pays homage to the influence and greatness of Killing Joke, which is fitting with the recent passing of Geordie Walker (to whom I have dedicated this year's AOTY list).

Thirdly, however, this is one of my favorite interviews I have ever done, mostly because it gets into all those weird corners I always love the most, having to do with art, how we make it, and what it means to us. But in a nice twist of fate it turned into a conversation about some of my all-time favorite metal bands and albums – Miasmatic Necrosis and Castevet – and, as such, also a discussion of a small obsession of mine – the New York avant-garde metal scene of the early 2010s. I have already talked to whole bunch of people about this general topic (Kayo Dot, Charlie Looker, Liturgy, Krallice, Yellow Eyes, etc), but this really wonderful talk with Ian brought a lot of the threads that came up here and there and tied them very nicely. [Fun fact, there's a huge interview I did at the time with Charlie Looker and Andrew Hock (Castevet), that I then buried because a lot of stuff was going down at the time. I might have to get back to doing it. I'll think about it.] Oh, and I almost forgot, we get to talk about basically my all-time favorite topic: metal drumming.

So, a top conversation with a top artist about some of the most affecting art in my life. All I can do is be grateful. I hope you enjoy it.

As ever, check out everything else I do in this dilapidated shack of a website, including interview projects and other cool shit. And if you'd like to keep abreast of the latest, most pressing developments follow me wherever (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Spotify and now also a tape-per-day series on TIK TOK!), and listen to my, I guess, active (?) podcast (YouTube, Spotify, Apple), and to check these amazing compilation albums. You can support my unholy work here (Patreon), if you feel like it. Early access to our bigger projects, weekly exclusive recommendations and playlists, and that wonderful feeling that you're encouraging a life-consuming habit. On to Ian.

Do you remember a moment in your life – probably as a younger person – with an album or a song or an album cover or a live show or whatever experience you had that really kind of rewired your brain as you're experiencing? Music that scared you or really shocked you or surprised you? And that maybe led you down a path of a life with music or something like that?

That's tough. You're asking me to go pretty deep into the well here. I don't know if I could really pinpoint one specific moment. I kind of see this stuff as a series of moments, just this continuous story and. You kind of find yourself on this path, and as you're on the path, you see these signs along the way that are pointing you into which direction as the path splinters off. I could say one of my…. I grew up, my first love, music-wise, was punk, and I think when I was in elementary school, maybe third or fourth grade. This is the early 90s, the skate punk stuff that was happening at the time. I must have been nine or eight, I was pretty young, and bands like NOFX and Rancid and all that stuff, getting into Green Day, around 94. And I remember that being the first, at least in terms of my trajectory as a player, that was the real fire starter, if you will. It was that music.

And I remember those albums very vividly from that time period. I remember hearing the way the drummers would play, and not really being able to understand how it was done and really trying my best to figure it out. This was before, obviously, the Internet and all that stuff, so it's not like you could see videos of these people playing – it was a real Pandora's box for me. And I think that, if I had to cite a particular moment in terms of what set me on the path that I've been on essentially my whole life, it probably would have been around then with those types of bands. Because from there, especially as a drummer: “How are they playing so fast?” or “How are they doing this?” And then as you start discovering the tricks by experimenting on your own, then hear the next thing. That's like just one step further than where you are, you know? And then eventually you go: “How the hell are they doing that!?” And that's kind of what led me to death metal, grind and stuff like that. Because it was like: “How the hell are those guys doing that?” I mean, I figured out some stuff but then you just keep going down and down and down.

So that brings up two follow up questions. One would be so the drums were always it for you….

Not necessarily. I mean, I do play other instruments. The drums are my primary instrument, they're the first instrument I took seriously. I did play instruments before that. I think the first instrument was actually a trumpet. But the drums were the thing I think I latched onto the most. And being kind of an angry young kid I wanted an outlet where I could play as fast and beat something as heavily as I could. But I wouldn't say that the remainder of the music didn't go unnoticed. I just think I focused on the drums primarily at the time, and as my musical vocabulary kind of expanded and as I started figuring out how to express the things I wanted to express on the drums, then I could start kind of focusing on other elements of the music, likeL “I really like this harmonic change. What is this?” I seem to gravitate towards certain types of melodies or keys. But the thing to start it was really the drums.

Just as a personal note, because Dookie was probably one of the first CD I've ever owned. Either that or Weird Al's Off the Deep End. That was probably my first CD.

Nice.

But one of the things about Tre Cool is he's a phenomenal drummer.

Yeah, very tight.

And I think very underrated, at least in terms of extreme music and drumming influences. He's not a name that comes up a lot. It's more Pete Sandoval and less Tre. But he has a great feel, and lovely short, violent fills.

And you know, to your point, I think that's the kind of thing that, as a drummer, as I've gotten older, the types of players that resonate with me more or that I tend to gravitate towards in terms of being inspired by them – it's not the fast people with like the really interesting Moeller techniques. Like I don't care about that stuff. It's all really feel, you know? And, to your point, Tre is kind of a perfect example of a player that.… I don't think that band would have sounded the same with a different player, and obviously that's kind of evident, because I think they had a different drummer originally and you can really just see the shift in energy because of the drums.

I'm a lifelong appreciator of drumming and of drummers, and I have a very long, very intricate, and very boring theory as to why that is. But, when I go to shows, that's where I look. I look at the drummer. I don't really care what else is going on, because if I'm in sync with that, it feels like that holds up everything. And that's obviously not to…. I mean, I don't listen to bongos, I listen to metal for the most part, and so I do appreciate the composite effect of everything coming in together. But I think it's almost undeniable how important the drums are. But being that usually drummers aren't necessarily always the main songwriters for bands, or, as it translates into the PR world, the spokespeople for bands, then it's not often that I get to talk to drummers. I mean, I think you're maybe like my third or fourth drummer ever, and I've done hundreds of interviews at this point. But, what I wanted to say is that one of the recurring themes in the interviews I've done is the importance of punk, not necessarily just as a musical form, but via the pragmatics of playing music, right? That if you're young and you don't know how to play an instrument, then it really helps that there's a kind of music that you can play that is very simple, that doesn't look outside your grasp. It's not like watching Tool for the first time and going “Oh shit, I can't do any of this!” You're watching something that's doable and approachable.

So would you say any of that played a significant part for you? The fact that punk was a good entryway for you because punk was there and doable, and made little Ian go: “You can actually do this!” and then bang it out and give it a go?

Yeah, although I don't know if I could really say it was conscious in the regard “Oh, I could do this.” I never really had that thought. Circling back to something you brought up before, even though I focused on the drums, it was kind of the energy and the aggression of the music that, at the time, I needed that vehicle to kind of express what I was dealing with, personally. And it just happened to be a perfect situation, a best-case scenario, where the entry level for it was pretty low, to your point, anybody can kind of jump in at any point of the story of punk and learn how to do it and play it. It's not as demanding, there are not as many expectations for you as a musician. Not to say that there aren't amazing players, and obviously there are…. But it was never the kind of thing of “Oh, I could do this.” It just happened to be the music that I think really resonated with me the most. And, hindsight being 20/20, it was perfect because it was the type of skill set that I was easily able to pick up, at the time.

But, back to the point about the energy of the music, that's the thing I've noticed punk still having an influence over my life, because I still love a lot of the bands I loved back then, and I still revisit that stuff every couple of years. And it still hits me, I still feel this sense of urgency. The majority of my bands have been metal bands, but I feel like every band I go into, I still want that sense of urgency, even if the songwriting is more long-winded, comparatively, to punk rock music. I still want that feeling. I still want that urgent motion in the songwriting that punk tends to have.

It's very interesting, actually, because…. I don't know if you've noticed, I'm usually a very distracted person in general, that’s kind of what defines me, I'm a distracted person. But this is a very distracting time for me politically and in terms of my fatherhood. So, I'm more distracted than usual, but I'm going to use that energy because one of the things I wanted to get to later, but I guess there is no beginning, middle, and end in the story necessarily, was how you drum and specifically on the Aeviterne album, which is why we're talking about. We can talk about Miasmatic Necrosis as well because, in a very unprofessional moment, I will say I believe it is a true absolute masterpiece that will live forever. Not that Aeviterne won't, but that Miasmatic Necrosis album, to me, touches on something that is timeless in metal. That I just can't get enough of.

Wow. Thank you so much.

That’s just a side comment. I could have said the somewhat cliche but kind of accurate question: “Hey, Ian, you're in a bunch of different bands and you do different things – Why is it that you do different things?” And obviously that has a kind of a self-explanatory answer, which is that you're a person that doesn't just want to do one thing. But if there is something that is kind of a common thread in those very two different albums – The Ailing Facade and Apex Profane – if I had to kind of pick your aura as a drummer, right? If I had to say…. You know Inter Arma right? You just toured with them I think.

Of course.

So TJ’s drumming aura is John Bonham. That's the aura. Big, sloppy, swing-filled. Everything is profound and deep, but also kind of drunk at the same time. And so if I had to, by contrast, to pick yours then I would say your aura is “manic.” And what's interesting about that idea in an album like The Ailing Facade is that the music, the melodies, the guitars, and even the vocals, to an extent, they're all kind of really stretched out and very spacey and lush. It's aggressive and it's beautiful, it's a wonderful album, I'm not just talking to you for no reason, I love it. But it's very atmospheric. But, you, inside that box, you're always at it. Every time a riff goes stretchy or kind of open, you're just banging every thing next to you. You're just banging the whole set the whole time, always, and forever. And so the reason I raised this now is obviously that I love that. I love bands that do that. It's a very…. I have my own examples of the kind of bands that do that some of them might not seem appropriate, but a band like Rosetta, who I love, who do a very different kind of music, but have that feel of like a very open-ended guitar section and vocals and a drummer that just is always kind of busy under it. And so I wonder are the two related? What you called a search for urgency and your tendency to stay active as a drummer?

Absolutely. I mean, I think you're kind of reinforcing what, maybe in a more eloquent way. What I've been trying to convey is that, and this is an unconscious thing, that what I want to hear, but also, more importantly, what I want to feel from the music. I don't necessarily consider myself the kind of drummer that needs to be soloing, it's just all kind of context, you know? And I think that in metal…. Metal, to me, to use a word you mentioned before, it’s an aggressive

form of music. So, especially when there's this open space, if we have in some of the Aeviterne songs these long open passages where maybe not a lot is happening harmonically, to me something still needs to be providing the sense of aggression or urgency, or continue the story. Because I feel like songwriting is essentially storytelling. Not to say that open space doesn't do that, but for me, fundamentally, that level of aggression is what makes metal metal. I listen to lots of different types of music, and it just so happens that the type of music I tend to play demands that level of urgency.

It's almost like this voice that says “urgency”…. Not necessarily heaviness, we're not talking about heaviness. We're not talking about riffing, right? We're talking about energy. Which is the word you've been using. So basically what you're saying is that if the energy is not coming from that part of the band, then it has to be coming from somewhere else. But there is no let up.

I mean, yeah, I think so. Again, it's intuitive. It's never conscious. When we write our songs, when I'm listening to the riffs that Garrett’s bringing to the table, I'm always thinking in terms of “Where is this taking me? What am I feeling from this?” And I need to reinforce that and keep it going. That's what makes the song what the song is.

Yeah. It's funny because a couple of years ago I interviewed the guys from Discordance Axis, who are one of the all time heroes to me in that kind of energy, in creating energy.

Yeah, Dave. Dave Witte is one of my huge influences.

So, I was talking to Dave and I said “Look, sometimes it's almost comical, it's almost funny or jazz-like. There is this discordant riff that's really chugging, it's not really doing that much, it's not grinding, and you're there in the background going nuts, as if the song is actually much faster than it really is.” And he mentioned that sometimes, this is just to your point right now about the dynamics of the band, that kind of dynamic was was because they were trying to fuck with each other, right? He thought it would be funny if during this dramatic discordant moment or breakdown he would just go fucking HAM in the background because it made them laugh.

[Laughs]

I love that. I love that kind of interplay within the band. I think it's great. But I also think there’s something…. Other than the urgency it provides, there's something very, I don't know if this is the right word, calming about it. There's something calming about the fact that the drummer is not beholden to whatever it is that the guitarist is doing, at least not in a follow-step-by-step type of way. There's something very freeing about it. I mean, that’s the drummer, the person supposedly isn't supposed to act out, and he is acting out, that he’s a person and a musician in that setting.

For me, creatively, that writing – circling back to you mentioning Castevet earlier – that, to me, was the beginning of me approaching music in that way where it was like: “OK, well, here's the riff, these are the harmonic changes in the riff that I’m feeling the most. So, instead of just trying to be like a metronome and just kind of back this up, what can I bring to this riff that isn't implicit already? What can I do with it that gives a greater depth and gives me that sense of urgency that I'm looking for?” And a lot of times it's something so fragmentary or small in the riff, or in harmony, or in the melody. I wish more drummers wrote like that in metal. There are drummers who do it. I remember when we started Castevet, one of the ground rules I had laid, because I had been playing with the brutal death metal band at the time. And I was so tired of playing blast beats, so the rule was: “I'm not doing it.” It seems like sacrilege, right? To say you're not going to play blast beats to some of these riffs, but I find that it was incredibly liberating for me creatively, to kind of make that executive decision that I'm going to limit the amount of cliche I'm going to use here. I wouldn't necessarily say I write the same way in Aeviterne as I did in Castevet, but I think there's a through line. In that it’s really a question of…. Obviously Aeviterne uses blast beats, and there's kind of more conventionality as far as death metal tropes are concerned. But there's still that influence of: “What am I hearing that maybe isn't being accentuated by the other players in the band? What other dimension can I add to this, as a player?”

I'm not a drummer. Had I been a drummer…. There's that old joke about drummers and metal, that essentially there aren’t enough of them, evidenced by the fact that every drummer has 19 bands, right? But had I been a drummer then I can see how I could easily fall into the trap of walking into that studio space and saying: “OK guys, what do you need?” Which is fine, I mean, that's being a nice person that's servicing the band and being a bandmate. But there's a problem with that in that you don't get to say what you want, right? And so I think even the fact that you were sick of playing brutal death metal, that you were coming off an experience where you said: “I'm not doing that, I'm coming in with restrictions.” The drummer is coming in saying that there's this part of drumming that you might think is relevant, but he’s not doing it, and by that fact becomes a person in that room, and say “no” to something. That’s already a very creative moment, if the band accepts it and everyone kind of works with it. Because you're inserting yourself into the music, you're not being OK with just being there.

To that point, even though drums are my primary instrument, I don't think of myself exclusively as a drummer. You said before about servicing the song, there's room for that in the music world. There's room for all of this, and there's a place and time for everything. It's just that I know my motivations as a musician well enough at this point to know that being a session guy and coming in and servicing [the song], that doesn't excite me. Not that there's anything inherently wrong with it, it's totally good. It's just that isn’t what inspires me, and it isn’t what motivates me. Being more creatively involved in the music is really kind of my focal point as a player.

I just want to say this as a kind of entryway into the workings of my mind. My #1 cause of stress right now and for last year is that me and my wife, we have three small children, and a lot of shit going on, capped by the fact that we bought an apartment and we have been renovating that apartment. I don't know if you know, but it's very stressful, a lot of stress on our relationship. It's never ending. There's always something malfunctioning. There's always something being too expensive. It's a lot of stress. And some of the decisions I made in the process had to do with a reaction to recent experience. So, for example, in the apartment we’ve been renting, there are laminate, fake hardwood floors, right? And we had a dog and the dog was old. We never cut its nails. So every time the dog would walk on the floor, it would sound like hell to my ears, like a typewriter. And so one of the first things I said about the new place was that this kind of floor is not happening. We’ll put in tiles, because that way the dog won't make that kind of noise on the tiles. So, the house is almost done. The tiles are there, because I insisted on that, and the dog has since died. So, the reason I wanted tiles in my house isn't there anymore. So, my first instinct is to say: “I guess I'm just an idiot now, right? I made this life-altering decision about how we live our life, which required me to force my opinion on my wife, because I really was adamant about this. But now the reason for that is gone.” And so I saw that as a point of failure for me, I guess.

But, if I'm learning something from our conversation now, you might not see the connection, but that being sick of something, being tired because of a very specific kind of experience, and being led from that into a different path is also kind of an expression of who you are. And whatever comes with that, whether the dog is alive or dead, Who knows? Who knows what kind of creative energy might be created as a result of an experience that really was for a moment just you being a petty person saying: “I'm sick of this shit right now, and in my new relationship, or my new band, I'm not doing that shit anymore.” Had you not been in the brutal death metal band Castevet you would have not have said that. And the band would have sounded different. So, it isn't petty, is what I'm trying to say. It's not petty, it's not just a whim. There is something fruitful about that. I'm sorry for that tirade. I really am.

No, I think that was a great analogy, honestly. I maybe zoomed out far enough from my life to maybe kind of think of it in that way. But it's interesting when you do think of it that way, or to use the analogy you put forth. A lot of my favorite musicians throughout time, going to somebody like Dave Witte, who we talked about before. Not only is he great in these individual moments of his life, but also watching their trajectory, watching him age into doing the thing that he's doing, seeing that all unfold over a much larger span of time is really interesting. A lot of the personality of musicians I admire, seeing them progress throughout time, it's not just about that one great album they did. It's always about how it fits in their trajectory of what was going on in the exterior of their lives, that kind of gives greater context. Because I could say the same thing, going back to the Miasmatic Necrosis record. I had been doing so much heady music at that point that I just want to make something that's very low-brain. So, it was a reaction.

Yeah, yeah! That’s the funny thing about it, the wonderful thing about that album. The fact that it distills so many beautiful things. Obviously, we're not talking about that right now, but when you listen to it and you feel like it's the first time I've listened to Carcass, or something. That's how I felt.

Wow.

And I think the reason it captured that feeling so well is because it sounds like the band is saying: “Hey dude, this is as knuckle-dragging as it can ever get. This is what it is., it's not more than that, it's not less than that. It is exactly that. And you will know it from the first kind of snare ping to the last snare ping about 10 minutes later.”

[Laughs]

You just realize that there is no pretension in this other than to fuck you up, and because that is the energy, then all I want to do is get fucked up. I don't want anything else like when that album is playing, I don't find myself. You know, longing for atmospheric passages, I'm like: “Yes, fuck the world!” [Laughs]

[Laughs] The way I approach that band is I just see it as reconnecting with punk. I just see it as a punk record, with death metal riffs. All of the song structures are so ABAB, really like punk songwriting. That's what it is. It's really trimming the fat and reducing it to its most essential components. And when you've spent a lot of time writing more complicated or involved music, it can be surprisingly difficult to know when to edit yourself to that severe of a degree. So, even though it's simpler music, it provides a challenge that maybe is unforeseen.

I mean, my day-to-day life is…. Well, it’s actually way too filled with this website. But, my real day-to-day life, the one that actually earns me money and all that, is surrounded by writing. And one thing I noticed about the trajectory of some writers, sometimes it's that trajectory, sometimes it's the reverse, either from simple to complicated or from complicated to simple, but it's always very clear to me, also as a writer myself, that the simple stuff is that that's the kind of stuff that feels to me beyond my reach. Like that feels like too difficult even to even imagine. Some people might listen to Rush and say: “I will never play drums like that guy.” I don't listen to Rush and think that. I think he practiced a lot, right? I, but I listen to something like, I don't know, John Bonham and think “I would never be able to get that feel. I will never do simple that well.” That is my kind of end-of-the-rainbow thing. And with writing it's very clear, because I write more like Rush than I do like Ringo Starr, and I hate it. I hate it. I really would like to write like Ringo Starr. That's all I really want to do. Or Dave Witte, for that matter.

And so I understand that, I think it's s a very important lesson, in what you said, in editing and trimming the fat. There's something very humbling about it. And it's also kind of exposed, right? Because you have to do a very simple thing, and if you don't do it right, then it's going to sound horrible as opposed to a nine- minute reverbed guitar chord, which you could always add another minute, it doesn't really matter. So the stakes are much higher in getting it right, I guess.

As I've gotten older, and the more I've done this and the more I've taken on new projects, and, to your point of: “I'll never be able to write like that person.” So, the more I've learned – and this is almost like therapy, music is therapy – to not trust my thoughts. To not take them as literal. Because a lot of times when I think something's impossible, I will it to become impossible. You can't make thoughts go away, but you can learn to not place such importance into them or take them seriously. Doing something simple or something more involved, depending on what the band is, whether or not I think I can do it or not, it's always just a question of: If I can just tune out the thoughts and tap into, again circling back to the the energy, and trust my intuition about what I want to feel, then I always find that, while it's probably a rocky road getting there, but you can do it. It’s just that a lot of times your own thought process tends to be the enemy of your creativity.

So, to that: To what degree is that process of tuning out, and maybe with time teaching yourself to tune out better, to or to exert less energy before you're able to tune out, and all those things, to what degree is skill a part of that process? Is it just “I've tapped into the energy, and if I can just find the frequency, I'll find it,” Or is there a moment where you have to wood-shed it? Banging at the drums for an X amount of time before you feel confident in accomplishing something?

Yeah, I don't want to devalue practice. I mean, do feel that, to your point, I don't think anybody can pick something up, whether it be music or writing, any skill set, and not have to practice it. I don't think there are people that are innately gifted towards certain fields, more so than others. But that doesn't necessarily mean that it still doesn't require work. I think work ethic is hugely important, but I wouldn't conflate work ethic with the thought process that you can kind of get lost in when it comes to actually executing the thing you need to do. To me, they're separate, and I still find myself having…. To go back to the Aeviterne record, all those drum parts required an intense amount of practice for me to get down. But, the point for me in terms of energy or intuition, is that what led me to write those parts was some kind of ineffable thing. That's why I say “energy.” That's why I say “intuition.” It's the years of listening and just internalizing music and what I want to feel from something. But then I need to develop the chops to be able to execute that thing I want to feel. It all kind of works in tandem.

Yeah, I get that. I just hate that chops part, man. I just hate it.

[Laughs]

That's why I was asking you about the skill thing, because I was wondering whether or not the feeling of confidence that comes with mastering the chops part, whether or not that helps with the tuning out part? Even though they're not related, even though the skill or the learning part isn't necessarily the energy and ineffable part, do you gain a sense of worth or confidence when you do the chops part well. Is there something that feeds the energy that comes from skill?

I mean, I would imagine it's probably the ego to some extent. Because it does feel good when you can obviously execute something really well. But, I tend to free associate, so my brain doesn't think of just music. I think of kind of everything in life and…. As you've mentioned with how busy things are for you, and the stresses you deal with, everything is a balancing act. And finding the right balance, there's no one-size-fits-all balance. It’s through the work that and through the practice and all those things that we're able to figure out what balance works best for us. This kind of goes back to what I was saying before about seeing myself more as a musician in a general sense than I do a drummer, because I don't really get off on the practice of playing drums. For me, it's just the vehicle to get me where I want to goI. Really put in the time and the effort to practice when I know what it is I want to express, and how I want to express it. And that requires a certain level of skill. But, I'm definitely the worst kind of drummer when it comes to practicing regularly and developing new techniques. I can't think of anything more boring, but that's just for me personally.

[Laughs] There's a huge relief.

I mean, there are a lot of other great drummers that work hard and develop new skills and techniques, and my hats off to them. I'm just not that kind of player.

I think it's a good thing. And I think I think more people who hate practice need to talk to each other and kind of mutually comfort each other.

[Laughs]

All the lazy assholes. But, really, because there is worth, you do get something out of, shall we say, being way of a system. Because you get music that feels alive., for people who are looking for that, right? The Ailing Facade was a wonderful album to me from the moment I heard it, I knew it was going to be one of my top albums for the year. I immediately loved it. Some people might listen to it and might think it’s just OK, and that’s fine. But I think my sense is that people who are looking for that, or who feel that way, in a kind of unconscious way, are seeking music that feels like that too. They’re looking for, I don't know, organic, lifelike things, something that helps them with their life, that isn't just what they listen to in their car because they're going to work. It's something that gives them life, it builds them. And so, all of those people need to listen to The Ailing Facade.

To your point, it's definitely not an album for everybody. I can admit and acknowledge that.

Yeah, but when it is for you, you know it. Just like any other thing, just like painting or writing, or even people. When you meet a person sometimes you know “I'm good for that person, and that person is good for me.” You don't have to be friends with everyone. It's just the law of life. Most people suck, so that's just fine. I wanted to actually get back to the Castevet context. One of the things that piqued my interest – and to anyone who's been reading my interviews, this is already like a dead beaten-down fact – but I stopped listening to metal almost completely from – let's bracket it with albums, so beginning at around Isis’s Oceanic and ending at around Wavering Radiant or Crack the Skye. So 2003 to 2009-ish. I was like: “I'm sick of this shit, this is like teenage stuff, way too on the nose for me, and I'm going to listen to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs for six years. That's basically what I did, which isn’t altogether a bad thing, they’re a great band.

And one of the things that brought me back was that I realized, and this is something I could have realized in the 90s that you could actually listen to extreme music and have that music be very clever and smart and kind of counter itself and folding on itself. And what happened was that I inadvertently fell into what was then the “New York avant-garde metal scene.” Krallice, Liturgy, Yellow Eyes, Kayo Dot, to an extent, Charlie Locker and his stuff. So, I listened to a lot of that stuff and I really didn't know why. I was gravitating toward a very specific geographically limited set of people. And Castevet was part of that. I haven't talked to a lot of people about this, I talked to Charlie about this and also with Toby about this, and, at the time, I talked to Andrew, to an extent about it, and to the guys from Yellow Eyes. But: Do you feel like that was really a thing? From the outside looking in, it was very clear that there were a bunch of bands in that general area that were all very weird in different ways, and they're kind of maybe playing off each other, maybe not. And I was never really clear as to whether that was ever actually a real thing, that there was a defined specific scene and that those bands were in interaction with each other. Obviously they knew about each other, but whether or not it was this hub of creativity that I imagined in my Tel Avivian mind.

I think it's “yes” and “no.” It's “no” in the sense that if you believe it in the way that the press outlets wanted you to believe it, that like all these people are hanging out and engaging, it was never anything like that. I mean, you can't fault press outlets for latching onto it in that way, because you’ve got to sell the story, and it's a much more interesting story. It just then becomes frustrating, from my end of things, when you're a creator and you're getting lumped into, and piggybacked onto things and bands that are great but really have nothing to do with what you do. I don't necessarily feel like I'm directly connected to a band like Yellow Eyes in any way, shape or form, just aside from geographical proximity. Great band, no disrespect to those guys, obviously, in any way, shape or form. It's just not my creative voice. I don't feel a kinship to it. As a creator, I should say. I do enjoy their music, but it's a separate thing.

But, to circle back to the answer, I would say “yes” to it being a special moment, and this is where things get entirely subjective. Castevet started when Andrew and I met in music school. And we went to school in Massachusetts. I moved to New York in 2008, and things had already been happening, to your point. Bands like Z's and what Mick Barr was doing, and bands like Dysrhythmia and then Krallice. At the time you had bands like Bloody panda. There was this kind music school sensibility that was then embracing its metal influences. And the reason I say music school sensibility is just because when you referenced this music could be clever or maybe not so on the nose. When I moved to New York in 2008, there was definitely something…. I hesitate to say “something in the air,” because that makes it sound far more dramatic than it actually was. But there was definitely something going on. You could sense that the way the bills were put together in terms of shows, which bands played together, it was really interesting. It felt like you had a lot of people that were kind of embracing their interest in metal that you wouldn't have anticipated. And I think that’s what kind of birthed that 2008-2011…. I jokingly call it “the blogspot years.”

[Laughs]

Because that was at the time where everybody had a blogspot where you could get a Mediafire link and download. It was just a really fertile time in terms of not only music creation, but music sharing, the Internet was playing such an integral role in people being exposed to all these new things. So I think it was just kind of this perfect scenario where you just kind of have this little wildfire that just kind of happened. At least that's how it felt to me, not necessarily at the time, but felt to me years later when I reevaluated and thought about how much stuff happened musically to me after I moved to New York in the span of 2008 to 2010. It was a lot. A lot of stuff happened. And it was hard to not feel like things kind of slowed down. And this is where it does get subjective, this is not everybody else’s experience, for sure. Some other band out there has a different story to tell about 2015, you know? But, those bands you referenced, it seemed like it kind of died out, a little bit, by that time. I think also maybe age plays a factor, because a lot of the people that I was interacting with at the time, we were all around the same age, and metal, punk, you know, it's essentially, I think, a youth culture, right? There has to be an old guard and then a new guard. And I think around that time there was like a readjustment period, where you had the kind of new guard coming in. So, it's not so much that it died, it's just the natural force of life. That as you get older, our priorities change and it's hard to keep that going what we had in 2008 or 2010. I hope that answers your question [laughs].

Yeah, completely. It's your answer. And I think that ties in very well with how I experienced that period. I readjusted into metal just as I found out that metal helped me concentrate, because I was writing my degrees. And so I just listened to music incessantly, and the louder it was, kind of harking back to my days as a teenager, the better I could concentrate. This is still the case – I guess I have some kind of undiagnosed ADD or something like that.

We all do [laughs]

Indeed we all do [laughs] The lost generation.

Yes

Or found, in terms. Of creativity or whatever.

[Laughs]

Anyway, my sense of it was that I was experiencing something in real time, while not being in that place at all. I wasn't in New York when that was happening, but I was still somehow experiencing it in real time, and finding weird affinities, even if the participants didn't find that affinity. By the very fact that I, the listener, not the writer, said: “Krallice and Yellow Eyes sound nothing like one another, but they do make shrieky music that I like.” And so in that they make that, they are of a team. And so I felt attached to that, in a weird way, and as a result also felt attached to whatever happened with Andrew. I felt very attached to that, I felt horrible with that. And also, adding spice to the mix with gentrification, which I think led to the fact that some of the major players had to leave, because I guess New York was not the same city it was when they moved into it.

So I kind of felt that in a way that I can say, if there was a blogosphere, if there was like a pirating music world in 1977 to 1981, that would have been like my punk, right? I could have been somewhere, or tape trading in the 80s, whatever. I can say I was there for it. And I think that much of my sensibility of who I am as a listener was shaped by those years. That's kind of like the prism through which I judge modern metal. Everything that stems from the 90s, like throwback bands that throwback to the 90s, none of that connects with me. That to me, is like a dead person. Wait, I’ll show you my shirt [Yes, surprise surprise, a Megadeth shirt]. I am the biggest Megadeth person, and so I can't listen to thrash bands. That's not what I do. That's not what I seek out as an adult. What I seek as an adult is very much influenced by a post New York 2010s world.

Can I add two things?

Yeah, sure. You can add three things.

To your point, and kind of circling back to something I said before. I feel like I started coming into my own creatively in Castevet. There are a lot of through lines, if you really wanted to search for them, in other bands that I did after that. And that's again another reason why that time period, to your point, 2008, 2009, 2010, around that time, I think a lot of us…. To again say, I think a lot of us were of the same age at that time, and you didn't necessarily have to be in that time or place, we were all kind of experiencing something collectively, even if you weren't there physically. And I'm sure, much like yourself, really kind of came into who I am now in that time period. So there's something there. You getting frustrated with metal and only listening to indie, or Yeah Yeah Yeah…. And I love all that stuff too. It's funny to think that, you know, Nile and Angelcorpse were releasing awesome records in like 2000, that was kind of like a really interesting time. But 2002 to 2006, when I think back on that time, it's like a dark ages. Because it was just all metalcore – not disparaging anybody who was into that stuff, but it’s not for me. As a metal fan, none of that spoke to me. And I kind of did something similar at the time, I started exploring other types of music. I started getting really into electronic music, that was like another huge component for me at the time, just because, again, to kind of highlight a shared experience of what we all had in that time, I think I was fed up in the same way that you were fed up. It just so happened that I happened to then be, and, again, this is subjective, to be in the right place at the right time. Being in New York around that time period, meeting like-minded people that would go: “Oh, you don't only like death metal? You also like avant-garde, classical music?” or “You like electronic music?” or “You're into prog? Oh, this is really cool”. You know, there's something there.

The funny part about that is that one of the interviews I did for the 90’s series I’m doing is with Renato of Disembowelment, which was basically his only interview in the last like 900 years.

God-tier band.

Indeed. And a God-tier person, a very nice guy. And one of the things I asked him was about all those clean passages, right? Like, supposedly this immense death doom album, that was kind of ahead of its time, yadda yadda yadda. And when you listen to it, parts of it sound like a Dead Can Dance album, right? These open-strummed chords and eerie vocals. And those are some of the best parts. And so I was asking about what the hell was up with that, and he said something like: “You know, I didn't like metal. I liked other stuff as well, and I listened to Chameleons UK,” or whatever. And so to use your phrase now, circling back to what you said, that sometimes the best metal albums were made by people who were sick of metal, to an extent, or had limits as to how much metal they could have in their life, they had to have something else in there as well. I think the other famous example is a band like Neurosis, right? Who started out, started a hardcore band and just started listening to New Wave, and whoops, you have a new branch of music being born out of that.

So, I think that, in a weird way, the “avant-garde” and the “founding father” are kind of intertwined. And you could say about bands like Carcass or Napalm Death. A lot of the really supposedly “meat and potatoes” metal bands are basically people who were sick of just doing one thing. So, ADD for life.

[Laughs]

So, I think I've taken up too much of your time. I did want to ask one specific question about The Ailing Facade because we never really got to the actual album, despite this being an interview about the album. I don't feel bad about that at all. And in fact, to show you how much I don't feel bad about it, the question is not going to be a very album-specific question. One of the things that is wonderful about that album isn't even the music, it’s how it sounds. And I know that you guys were very specific about looking for a specific kind of sound. And seeing how differently it sounded from Sireless, just talking in terms of the aesthetics of it, then I would like to know more about that. Was that a big a part of the album? How it's recorded, how it's engineered, how the drum sound, because they sound fucking amazing. How important was that for you when you were constructing the songs and when you were recording?

It's funny that you say you don't want to take too much of my time, but this is one can of worms, this topic. So, prepare yourself [laughs].

[Laughs] I am prepared.

I don't know if you know this, but Colin Marston engineered the drums, but that was only because I didn't want to have to record them. Everything else was recorded and mixed by myself.

Oh wow, I did not do that.

So, I don't know if people…. And I get it, Colin’s is a household name, and it's easier in press blurbs to be like: “Produced by Colin Marston.” But, the reality is he recorded the drums because…. Well, the last thing in which I recorded myself before that was the Miasmatic album, which I also recorded and mixed.

Unbelievable. It sounds unbelievable.

Thank you. There were just things during the tracking of the drums for that record where it was: “Oh, man, that mic moved and I didn't notice because I'm trying to focus on actually playing the kit.” And it was through that experience – and the idea of reacting to a previous experience comes back into play here – I just couldn’t do that again. And the parts for Aeviterne are way more demanding than the Miasmatic ones. They're both demanding for me, but just in different ways. But I didn't really want to skimp on it for the Aeviterne record, I really wanted someone there who can kind of keep watch on everything, so I can just focus on playing.

The production of the record – I would say the sound of it was a huge component, because all of the songs were very extensively demoed before we actually tracked them. So, we kind of had an idea already in place of what kind of effects we're looking for. To give you an example: There's the instrumental track at the end, that is essentially a couple of layered, pretty crappy-sounding acoustic guitars that have just been processed a million times to make it sound the way it sounds. And, again, that was all deliberate in the creation and writing of the record. We kind of want this effect here – not an effect as in an actual effect, like a delay, more the emotional [effect], the impact. So, we want this feeling from this part, and this is another hard lesson I learned in the production of this record – I tracked everything aside from the drums, with Colin’s amazing help. But I had kind of gotten to the point where I needed to distance myself from it. I'm too deep into the painting to be able to see the frame, so it would probably be helpful for me to outsource the mixing. And we did that and went to a great engineer, but it became evident that, again, we already had something so specific in mind that bringing somebody in…. I would use the analogy of picking up a book and starting halfway through the book. The engineer was kind of like: “Alright, well, I can kind of guess what's going on from pages 100 to 200, but I'm still missing the context of 1 to 99.”

And we did a lot of back and forth drafts on that, and we ended up scrapping the mix. And the reason I bring this story up is just to kind of give you some context that, yes, the sound of the record was a huge [laughs] part of not only how we wanted to come across, but why it took as long as it did between Sireless to The Ailing Facade. There were countless times on the record where it was like we're looking for this type of impact from this thing and it just takes hours “Well, I'm going to try reamping this with a weird effect,” or “I'm going to take this acoustic guitar and I'm going to run it through a synth and screw around with it through the EQ and see what happens.” There were so many hours of experimentation. And doing that with an engineer that you're paying to do is not exactly the best use of time and resources [laughs]. We're not a band that makes money. But, even throughout all that, there was still no compromise in terms of what we wanted the impact of the sound to be. So I would say the sound of it was vastly important, and I think you had commented on maybe a progression in sound between the albums.

Yeah, definitely.

I would say there were two reasons for that. One being, obviously our ambitions creatively just kind of got bigger, the scope of things got bigger. Sireless was like a demo, a jumping-off point. The template that we want to work within and naturally try to expand upon on the album. But then also, two, having the experience of recording this project and that project, my abilities as an engineer and mixing engineer just kind of broadened over that time period as well. So it became a bit easier for me to pinpoint, maybe sonically, how to achieve certain things that we want to feel from the music.

Not that I think that you thought of any of this during that kind of exploration through the jungle for the right sound, right? But when you listen to the album now, do you feel like there are albums, not necessarily metal albums, that you feel may have been or are related or like in the family tree of how it sounds? Because to me it sounds like – I'm kind of repeating myself here – almost like a post punk or new wave vibe to the sound. Not necessarily because of the electronics or anything like that, just because of that reverby, bright sound. So is there anything you can think of that might seem to you related?

I mean, I wouldn't say it's a one-to-one relation, but we all share a love of Killing. Joke, kind of all periods of the band.

All humans should have a love for Killing Joke, of all periods.

[Laughs]

And the prime example of a band that progresses over time and changes over time. Like we said at the beginning, Killing Joke is the template for that. Because they're still making albums, and those albums are still amazing. But, sorry, I didn't mean to interrupt you.

Well, Youth, as a producer, I think is really interesting because if you look at Absolute Dissent or any of the newer records, they have a quality to them…. And, again, bringing back up the topic of your thoughts being the enemy of your creative process, that you can get really lost in what “objectively good” sounds like or in the same way of drumming, what “objectively is good” technique is. Those are really hard things to let go of. But, Youth on the newer Killing Joke records, they sound very uniquely him. I can't really pinpoint exactly what the mix of a record like Absolute Dissent sounds like. It sounds just like a Youth record and a Killing Joke record and I've always.

That's such an amazing feat, to pin down your voice as an engineer on an album.

This was actually something that Sam, our guitarist, said to me when we were talking about the mix of the record and. I'm going to misquote him, but the essence of what he said in this moment is somewhat true. That it doesn't matter whether it's objectively good or not, it suits what the thing is. It's right the way it is. And, again, you can get lost in the anxiety spiral of your own thoughts, like: “This isn't good enough,” or: “This isn't it.” What I was gonna say before is when I first started recording or getting into that, what led me into that were bands like Trans Am or Zombie, who were producing their own records. That to me was really inspiring – how personal this thing that they're creating goes to the finish line. Like, objectively, the best mix in the world is just a question of whether it's true to the band and true to you as a creator, and Killing Joke, again, kind of going back to them, I think Youth is a great example of that. And they were another band that, going back to their earlier records, even just the implementation of electronics where it's not so obvious. It's not like: “Hey, here's an electronic part.” It's all supplementary. And there's still that energy there. Again, that punk urgency. Those are aggressive-sounding records. There's not a blast beat on the damn records, but they're still so urgent, and angry, and anthemic. So, to use post-punk as a kind of reference, that would be a major influence. Again, not a one-to-one thing. I don't think you could take The AIling Facade and put it against a Killing Joke record and say: “Oh, they use this as a reference to the mix.”

That connection completely makes sense to me. I was kind of hoping you would say that. My hopes have been answered, at least in that regard.

Well, you're welcome [laughs].

But, I mean, that's a very interesting idea, right? This idea that everything about whatever it is you do is personal. I remember this coming up not necessarily in terms of sound, but in terms of the visuals, when I was talking to Terence of Locrian, because he was inspired by bands like Sonic Youth – a close second to Killing Joke in terms of immaculate discography. And one of the things that Sonic Youth did was, for him, this is me quoting him, was to take the whole object seriously, right? So, in their case, the cover is not just some thing we slap on.It’s this amazing photographer that really fits the vibe of what we're looking for in the songs, and so on. And even that word “engineering” makes it sounds like it should be objective, like it's some science: The science of placing mics next to instruments, when really, like you said about the electronics in Killing Joke recordings, everything is just a tool in your box, and it's you using those tools – whether it's engineering, or the production, or the cover, or the lyrics, or your choice of who interviews you about the album a year too late. All of those are at your disposal, right? So, it's not a question of using them “correctly,” it's making sure that you're using it your way. And that sounds like your process with the sound of the album, right? That you were very adamant that it had to be your way. And you're looking for that way. And even though it took three times the time it might have taken to record that, what you achieved, what you ended up with, was your way. It’s such a powerful, yet impoverishing thing – it takes away all your money.

[Laughs]

Like choosing tiles. Look at that, look at that, all these threads coming together like a sweater. It's very hot in Israel right now, so just thinking of a sweater makes me want to escape this car.

It's been hot in New York too. So I feel your pain.

Jesus Christ. So I want to end this wonderful conversation. Really, I want to thank you, Ian. I want to personalize and then depersonalize at the same time. So, this was a very meaningful, important conversation with you, which made me remember why it's important for me to keep in touch with people with which I can talk about these things that are important to me. Because otherwise I turn into a crank and so, thank you for that.

It's really funny how social interactions, how much they give us and how little we tend to value them [laughs].

I mean, yes, but also because this specific brand of social interaction is something that I had to learn to accept as social interaction in my life.

Sure.

Because it could also look like me walking with a laptop into my car and talking to people I don't know on Zoom. It could be that. But, just as in production and engineering, since I am already the kind of person who turns things into what I need from them, then it’s an important moment of being able to do that, because sometimes in life you get swept up and you don't do those things, you gotta have to do. You don't do the things that you actually need to do, and you put them to the side because there isn't enough time and because the children will starve, or something like that. So, at some point these conversations have taken on the character of me trying to find answers for things that if the person I'm talking to is trying to find as well then it's going to go well. And the success rate has been pretty good. I guess I'm good at picking the people I want to talk to.

So, the last question after just, for no reason, giving myself a compliment in the middle of an interview, is a return to a set question. I have a set first question and now I have a set last question. And the set last question is, well, you might have answered it right now, but is there something about that album that, despite all things imperfect in life, that you are still extremely happy about? A choice you made, a song, the sound of it might be it. Anything about the album that when you think of it you say: “I'm very happy we did it that way.”

Oh boy, this is a good question. Let me start by just saying in the most general sense, I have no regrets with the album. I think, again, if you're true to your intentions and to what you're feeling and what the music makes you feel and responding to that, you can't make the wrong decision. I look at all of the bands I have been a part of, and I’ll use The Ailing Facade as an example, as definitely a product of that time period of my life. And I'm very proud of it, because I really think it accurately summarizes a lot of what was going on with us as a band, and what was going on with me personally. And I also think it marks a certain level of progress from the things that came before. If you're not going to challenge and kind of push yourself, to me, that's…. I don't want to be such an uptight ass about this and go: “If you're not challenging yourself every single time, it's for nothing!”

But, challenging yourself is fun. You know, progressing as a human, I mean, you're still alive. You're still here [laughs].

If I may interject, that makes it something that is a little more than fun. Because, if the end product is “You’re alive,” then challenging yourself means being alive.

Yes.

So it's fun in that you are alive. I just wanted to add that.

Well, it's like what makes roller coasters fun, right? They're scary as hell, but you walk away from it being rejuvenated, you know? I put a lot on the line for that. I mean, this is a poor analogy, but hopefully you understand.

No, it's fine. I'm working with it.

[Laughs]. But yeah, I'm proud of everybody in the band for what they contributed to it, and that everybody stepped up to the plate. We went through a lot of gear issues, and re-tracking things, and everybody placed their utmost faith in what we were doing. Everybody in the band Garrett, Sam, Eric, everybody, myself. It was a true test for us as a band, and we came out on the other end with something we can all be really proud of. So, I am incredibly grateful to have those people in my life. I hope I've answered your question.

Your hopes have been answered. And my question. Everything has been answered. Really quite wonderful.

OK, cool.