NINE BOOKS I LIKED THIS LIFE IN LIST FORM

Maybe it's the winter. Maybe it's the war. Maybe it's me sitting in this winter and in this war listening to Bell Witch. Whatever the case may be, I thought this could be something to do. I deal with words every day, and I have been dealing with words my entire life. It hasn't always been fun, but at times it has. So, fuck it. Keep safe and warm wherever you are, and don't forget: Use Bell Witch responsibly.

1. Knut Hamsun – Growth of the Soil [Markens Grøde](Gyldenal Norsk Forlag, 1917). I think about this book almost everyday. In some ways this is the Burzum of the bunch, seeing that it's a) Norwegian and b) written by a gentleman of dubious politics. And yet unlike Burzum I think I can't really imagine my life without it. The power here isn't in the crazy riffs, or the experimental song structures, but in an almost impossible simplicity. A man moves into a wild piece of nature, and slowly builds his life up into the complicated mess of love, relationships, money that everything ends up being. Love is an underrated aspect of it, I think. To me the image of the protagonist Isak trying to carry a whole tree log by himself in his silent, humble attempt to impress his wife, Inger is not only one of the most genuine depictions of inept love, but a running joke in my house forever (everything can be a log-carrying exercise of love, from doing the dishes to getting something fixed around the house). FFO: Esoteric, Fange.

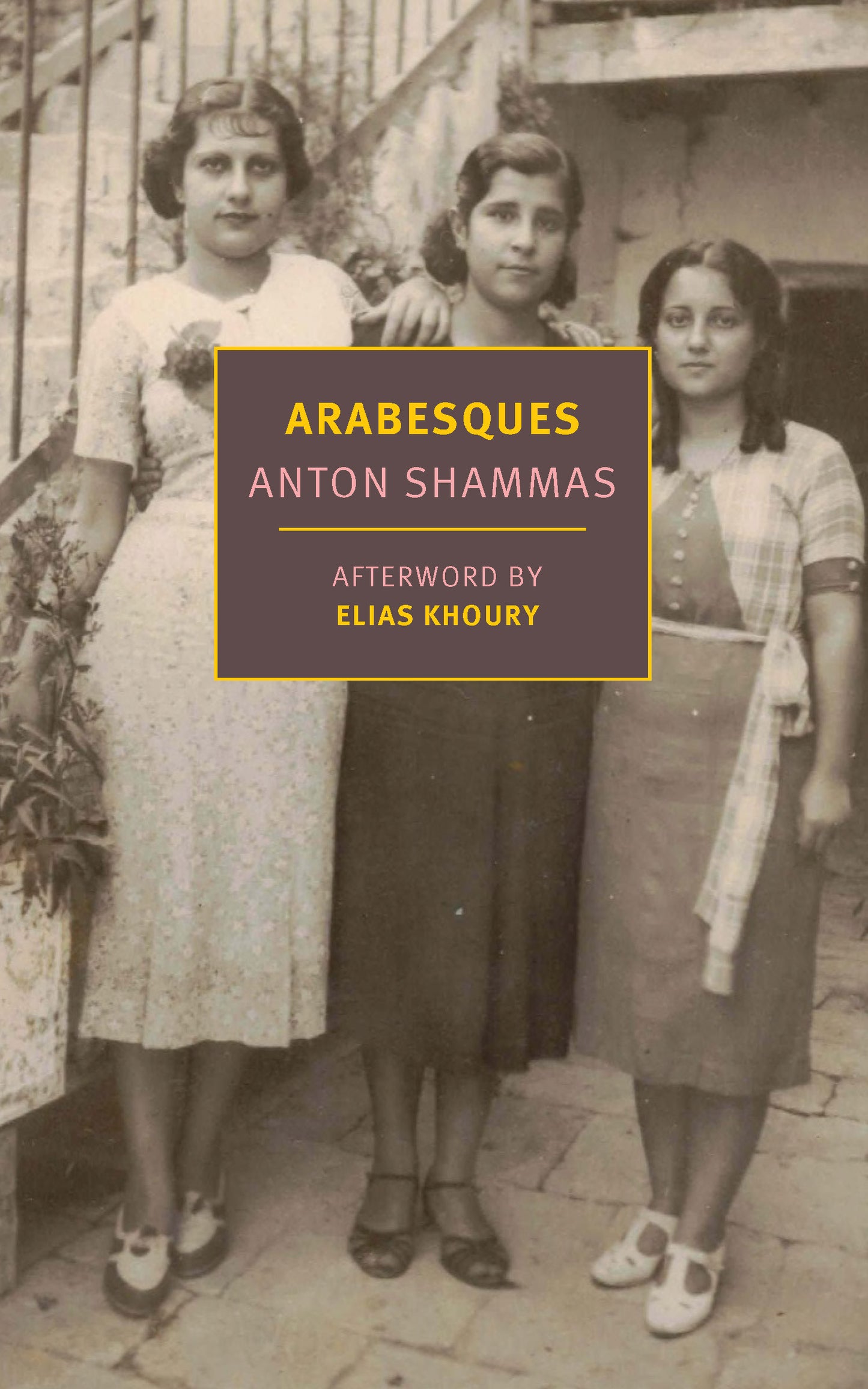

2. Anton Shammas – Arabesques [Arabeskot] (Am Oved, 1986). This, here, is not about simplicity, though simplicity is important. What's simple about it is the story: A family from the Christian Palestinian village of Fassuta is torn to shreds by the realities of two wars – 1948 and 1967 – sending various members to find out, the very hard way, what it means when borders move and politics change. The complicated part is how strangely and wildly lives intermingle and interchange, and how the past continues to fester and influence the present. When I wrote my own books I thought they were weird in that time shifted and made it difficult to follow, but I knew it was my way. And then I read Arabesques and felt completely at home. Not sure any of this makes sense, but it does to me. Home, that simplest of places, as the ultimate convoluted space. There's also a new version of the English that came out relatively recently, so I would get on that. FFO: Scarcity, Opeth.

3. Virginia Woolf – Mrs. Dalloway (Hogarth Press, 1925). No one in human history, maybe other than Shakespeare, was better at seeing humans than Virginia Woolf. I take that back – no one in human history, period. Imagine placing the most sophisticated antenna on your head, plugging it into your central nervous system, and allowing you see the very real, painful undertow of every small, minute situation of everyday life. Woolf doesn't write about "big things," at least not directly. She writes about humans being crushed by big things, whether those things are war, being a woman, being a man, being a child, being an adult, money, class, race, or politics. I can't think of a single thing that is more important to me when I read books or think about books – that feeling of someone being crushed. Silently, of course. Silently. FFO: Sweven, Kaatayra.

4. Orly Castel Bloom – Dolly City (Zmora Bitan, 1992). Another person being crushed, I guess. This time it's the dystopian, violent, personality-altering, earthquake of emerging into motherhood. I read this for the first time not long after we had our first baby (who is now a beautiful, brilliant girl of nine, and change) and thinking to myself that this horror-filled, graphic, ruthless dystopia is the closest anyone has gotten to getting to the feeling of becoming parent. Not unlike Arabesques, it was and remains a book so crazy and unhinged that it made me feel OK with being as crazy and unhinged as I probably get when I write. FFO: Cannibal Corpse, Pharmacist.

5. Giambattista Vico – The New Science [Di Scienza Nuova] (1725). Not technically the kind of book that would inspire anything, since it was written as scientific exploration into the roots of human culture and politics. But, regardless of how it was intended, it delivers one of the wildest, most imaginative and at the same time meticulous and studious rides ever. Some of the ideas here have become quite influential in the early part of the twentieth century, like, famously, the notion of ricorso, or the circular nature of human history. But to me some of the most moving sections have to do with the birth of language and the inherent violence that lurks both in that birth and in language more broadly. A unique undertaking by a supremely unique person. Happening to be next to his house when I visited Naples remains an all-time moment for me. FFO: Meshuggah, Froentierer.

6. David Jones – In Parenthesis (Faber and Faber, 1937). For those of you who might not now, my day-to-day is being knee-deep in war literature. Actually war has already been featured in two of the previous entries, though in a different way (Mrs. Dalloway and Arabesques). But, for my money, this humble tome is the best expression and depiction of war ever achieved by a human, ever. So much humanity, so much beauty, so much horror, and even some between-the-lines humor. Your'll never be happier reading about a rat eating a person. FFO: Ved Buens Ende, Immolation.

7. Herman Melville – Moby Dick (Richard Bentley, 1851). It really is kind of funny how a lot of these books were books I read because I forced myself to teach them in order to find an excuse to finally get to them. I read it the first time as a student, but spent some REAL quality time with it as a teacher. Melville, perhaps not unlike Jones and Woolf above, is one of those human robots who are incapable of writing a meaningless word. It's not a short read, and yet every word is charged with the desire to dwell on it, as if it isn't a novel at all, but a very long poem. I get why some people would hate it. For me it's a masterpiece unlike any other, in that it's main drive isn't about a story but instead on how stories or the stories we tell ourselves can be a very, very dangerous thing. Lethal, in fact. FFO: Not Mastodon. That album is fucking horrible.

8. The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens and Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson. A bit of a cop-out on the poetry section, I must admit. But I wanted both and I couldn't pick one, so there you go. In some ways, very different collections since Stevens and Dickinson were very different poets. But, to me, they kind of sit in that wonderful part of the brain that makes absolutely no sense and makes you cry at the same time. And they feel illegible in a similarly cerebral way, as if someone is talking to you in either logical formulas (Stevens) or a scary familiarity (Dickinson) and you take them very seriously, and yet they take advantage of you doing just that and short circuit the entire structure of meaning. It's almost like some of the best, most well-constructed stand-up jokes but they aren't (for the most part) funny. FFO: Virus.

9. W. G. Sebald – Pick Any of His Books, Seriously, but Austerlitz Might Be My Favorite (C. Hanser, 2001). Sebald is one of those writers who never wrote an un-beautiful word. In this case, as with some of the others, he's leaning HARD on what appear to be real people, real historical events, down to the photographs and architectural sketches. But, again, he uses those "facts" to create some of the most haunting, human atmospheres and situations imaginable. In that way Sebald is almost the modern offspring of someone like Daniel Defoe, who might have been the greatest ever to pull that trick – turning mundane facts into a tragedy of human suffering and coping. FFO: ISIS, Infernal Coil.

אתה גאון

אתה יותר כנראה ממני